LOW OIL prices are not good for the Nigerian economy. In its latest forecasts, the IMF's predictions for the Nigerian economy in 2015 have been cut—from over 7% growth to about 5%. The naira, Nigeria's currency, is doing badly. But what are the effects of lower oil prices in different parts of the country?

If new research from two Oxford economists is anything to go by, people in the largely Christian south of the country will do worse than those in the largely Muslim north. The paper looks at the human impacts of oil-price changes. It uses data on 34,000 women between the ages of 15 and 49 taken from the 2008 Nigerian “Demographic and Health Survey” (DHS). Nigeria started producing oil in 1957; the DHS has data on those born from 1958 onwards. The authors compare various measures of well-being to the price of oil in the year that a given person was born.

The authors find that in some respects southern ethnic groups benefit most from higher oil prices. Compared to those in the north, dearer oil is linked with an increased likelihood of southern women having a skilled occupation and being in work. Indeed the authors find that economic activity—which they measure by looking at the intensity of night-time lights in each region—does differentially increase in the south in years of higher oil prices.

Why does the south benefit more than the north? It may be because the government, flush with oil rents, increases demand for service-sector industries in the south. But that story seems unlikely: after all, for long periods of the time under investigation the north was politically dominant. If any region was going to benefit from government largesse, it would be the north. The explanation could instead be to do with how northern elites used oil revenue. As David Bevan, of Oxford, and others have argued:

the North-South divide widened during the 1960s and 1970s despite the political dominance of the North. The latter's growing economic inferiority may have been at the root of the reluctance of the Northern elite to rely upon market mechanisms or to relinquish control over the distribution of oil revenue.

So it seems like people in the south did best because of better economic policy. But there is a sting in the tail. As recent research has suggested, short-term improvements in your economic situation can be bad for your health. In this particular case, what economists call the “substitution effect” may be in operation. Higher wages make leisure for southerners relatively more expensive: if they take time off they give up more money. As a result, parents have less time to devote to their children—or at least feel that they do.

The consequence is that parents in the south may “reduce many early-life investments in their children”. No wonder, then, that a 10% increase in oil prices lowers primary-school enrolment by 2.1% and the number of primary schools by 1.5% in the south relative to the north. Some vaccinations also fall. Children in the south may be richer; but they may be less healthy.

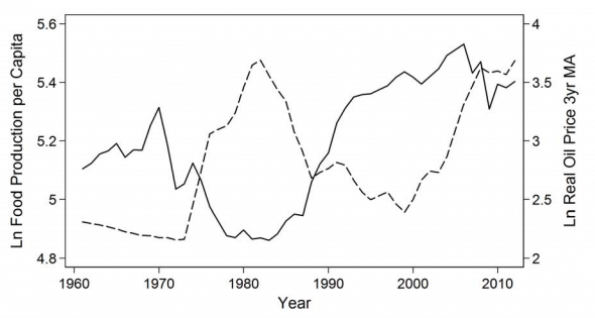

That’s not all. Higher oil prices lead to the Nigerian currency appreciating in value. That makes agriculture relatively less competitive, so production tends to slump (a phenomenon related to “Dutch disease”). The following chart, which plots Nigerian per-capita food production and the oil price, is pretty stark:

For a number of reasons, the south may have particularly suffered from poorly-performing agriculture. For instance, the authors argue that wages in oil and related sectors are especially high in the south, meaning that southerners might be more likely to abandon farming jobs. That would push up the price of food.

Dearer grub and busier parents exert a negative effect on a child's development. A southerner born during an oil-price boom is likely to be relatively shorter than a northerner, which indicates that they are less nourished. Such people were also relatively more likely to be obese which, as we have discussed elsewhere, is another sign of malnutrition.

It is impossible to know whether the effects found in this paper will apply to today’s falling oil prices. But if they do, then people in the north of the country may do better than the south. It's also further evidence that, though richer people are healthier in the long run, sudden improvements in economic circumstances can have undesirable side-effects.